Why to Use Phase-Correction Coatings for Prisms

Authors: Pierre-Alain van Griethuysen, Matthias Knobl, Gary Pajer

Examples from Galileo Galilei to Today’s High-Performance Binoculars

In the early 17th century, with contributions from a few well-known individuals like Hans Lippershey, Galileo Galilei, and Johannes Kepler, the telescope was invented. Not only was it the beginning of scientific astronomy, but also the establishment of one of the most important optical instruments in the world.

Keplerian Design for Modern Binoculars

Today, optical designs inspired by either the Galilei or the Kepler telescope are everywhere, from observatories, laser beam expanders, to theodolites. One of the most popular developments for consumers and everyday life are binoculars. However, for such handheld devices, a new challenge had to be overcome – Kepler’s design, with a positive ocular lens assembly, is preferred due to the larger field of view, but this design results in an inverted image for the observer (Figure 1).

Prism Assemblies in Telescopes: Design and Key Considerations

An inverted image may not be a problem for a stationary astronomic telescope, looking at mostly round objects in space, but for taking in the scenery or spotting wildlife, it is clearly not ideal. The solution comes in the form of image rotation prisms, namely the Double Porro (Figure 2) or Schmidt-Pechan design (Figure 3). Although these assemblies look very different, they both use a combination of internal reflections to create a 180° image rotation, which can compensate for the inversion in the telescope setup.

A very welcome side effect of these prism setups is the folding of the beampath. By design, the magnification of a telescope is directly proportional to the optical path length between objective and ocular. By diverting the light through the prisms, the beampath length is increased without the need to increase the physical length of the system.

Advantages of Schmidt-Pechan Prisms in Binoculars

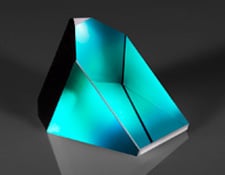

The collinearity of the entrance and exit beams in the Schmidt-Pechan setup allows more compact systems compared to the Double Porro design (Figure 4), making the Schmidt-Pechan prism a very popular choice for modern, compact binoculars.

In its most basic form, the Schmidt-Pechan prism combination consists of a Schmidt roof prism to correct the image inversion, and a half-penta prism to compensate the 45° beam deviation caused by the Schmidt roof prism. The two prisms must be air spaced, as the design requires two instances of total internal reflection at the two prism surfaces facing each other. A common solution is to use precise edge spacers to maintain the air gap between the prisms, then cement two extra glass plates onto the sides of the prisms to hold the assembly in place. Another aspect where the Schmidt-Pechan setup excels is the long beampath. Incident light takes a full loop through the elements, resulting in an optical path that is significantly longer than the prism’s physical length and thereby increasing the binocular’s magnification. However, since the Schmidt-Pechan setup incorporates a Schmidt prism, and thus a roof prism geometry, it does have some limitations inherent to roof prism systems, even if they are not immediately apparent.

Phase Shift Caused by Total Internal Reflection (TIR)

To understand these limitations, we need to investigate how the beam behaves around the roof surfaces. In roof prisms – like the Schmidt prism – light reflects off both angled surfaces (the “roof”) using total internal reflection (TIR). TIR does not cause light losses (like a mirror would, for example), meaning it provides practically lossless reflection. However, a deeper look into the Fresnel equations reveals that TIR introduces a phase shift between s- and p-polarized components. What is more, in our Schmidt-Pechan prism combination example, this phase shift may differ depending on the direction at which the beam enters the prism combination: a beam entering the left prism half may experience a different phase shift than a beam entering the right prism half, depending on the initial incident polarization.

An illustration of this is shown in Figure 5, where the portion of the (diverging) beam that enters the “green” half of the prism is reflected on the back roof surface outlined in green, then falls onto the front roof surface, outlined in red. Light entering the “red” half of the prism will go through in the opposite order. For most given polarization directions of the incident light, the projections of the polarization vector differ between the two surfaces, and so will the induced phase shift when the order of reflection is reversed. Detailed calculations, averaged over all possible polarization directions – as with natural, unpolarized incident light – reveal a net phase shift between the two paths.

In typical configurations, the light cone of each image point passing through the prism will be recombined in the image plane. The relative phase shift between the two halves will cause interference effects, creating a diffraction pattern, which will result in a degradation of resolution. Notably, this effect occurs only in the axis perpendicular to the roof edge which means it will introduce astigmatism. The distortion can be very easily visualized by taking an image of a USAF target through the individual Schmidt prism (Figure 6, left-hand side). The contrast on the horizontal line pattern is reduced, which is clearly visible in comparison to the vertical pattern. For higher-end applications, this reduction of image quality is not acceptable.

How Phase Correction Coatings Prevent Phase Shift in Roof Prisms

Considering that the root cause of the phase shift is total internal reflection, a simple metallic mirror coating will avoid the loss in resolution. However, the typical reflectivity of such coatings is in the range of 95%. As the light beam hits both roof surfaces, this would mean absorption losses of 10% of the incident light. For any device that will also have to perform at low light levels – like a commercial binocular at dusk or dawn – this is a significant drawback.

A more elegant solution to the problem is a so-called phase correction coating. This is a multi-layer, all-dielectric coating that compensates the phase shift caused by the Fresnel reflection and consequently avoids the resolution losses. At the same time, it leaves total internal reflection unaffected and uses materials that are absorption-free in the visible spectrum, ensuring lossless throughput. First patents on this topic were filed in the 1950s, and today almost no high-end binocular is sold without some sort of phase correction coating.

Edmund Optics is the first component provider to offer an off-the-shelf solution, using its own, newly developed coating design. The initial product is a Schmidt prism with 45° beam deviation, but the coating formula can be adjusted for different geometries and deflection angles on request.

Demonstrating the performance of the coating, the right-hand side images in Figure 6 were taken through a prism with the phase correction coating. The astigmatism is fully corrected, and contrast is equal for both rotations.

Conclusion: Phase Correction Coatings in Modern Optics

In conclusion, the phase correction coating represents the optimal solution for optical instruments that require an upright image without sacrificing image quality or throughput. The astigmatism inherent to TIR in roof prisms can obscure fine details or lead to eye strain as the observer subconsciously compensates for image imperfections. While alternative approaches exist, they typically reduce throughput – acceptable in applications with abundant light but limiting in scenarios such as binoculars used at twilight or surgical microscopy, where high-intensity illumination may be detrimental to living tissue.

or view regional numbers

QUOTE TOOL

enter stock numbers to begin

Copyright 2023, Edmund Optics Inc., 101 East Gloucester Pike, Barrington, NJ 08007-1380 USA

California Consumer Privacy Acts (CCPA): Do Not Sell or Share My Personal Information

California Transparency in Supply Chains Act

The FUTURE Depends On Optics®